Written by: Elisabeth Bienvenue

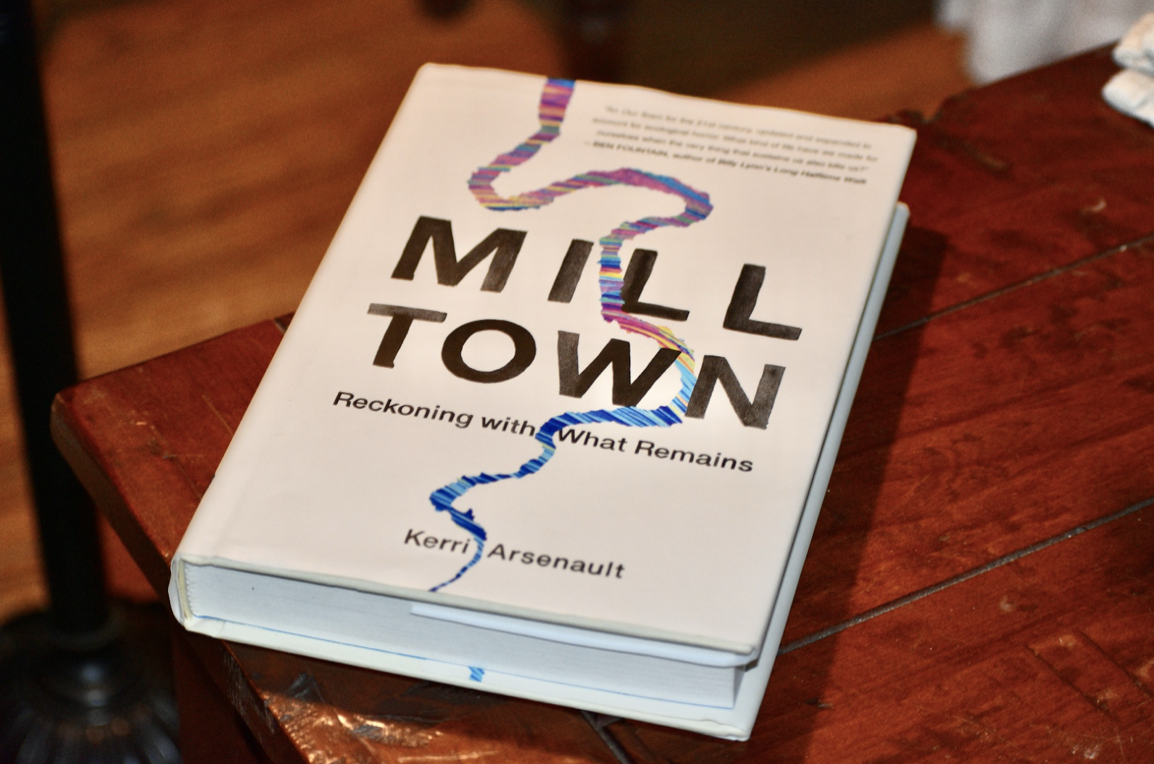

An illustration of a painted kaleidoscopic river slices through the cover of Kerri Arsenault’s 2020 book Mill Town.

I read the book and thought to myself: This is it. This is the book I want people to read.

In Mill Town, Arsenault braids together memory, genealogy, and history into a book which can be described as both memoir and environmental exposé. The river on the book’s cover represents the Androscoggin River in Maine, where traces of dioxin in the water left over from the twentieth century paper milling industry there continue to wreak havoc on the river’s surrounding communities.

Though Arsenault’s prose is tranquil, the underlying story in Mill Town is not. After the local physician realized in the 1980s that millworkers and residents of Arsenault’s hometown Mexico and the neighboring community of Rumford were dying of cancer at alarmingly high rates, it became apparent that dioxin, a chemical byproduct of the paper bleaching process from Rumford’s paper mill, was contributing to the untimely death of those who worked in or around the mill.

Arsenault spends her book grappling with the personal and environmental impacts of the mill. By collecting the histories of Rumford and Mexico residents (including poignant memories of her father and other family members), she effectively documents those in Rumford and Mexico who were affected by the mill, and she shares the accounts of small organizations such as the “Toxic Waste Women” who worked to advocate for victims.

Most importantly, Arsenault humanizes the victims of high dioxin levels and shows the profoundly dangerous consequences that occur when the government does not regulate toxins stringently; more often than not, legal amounts of toxins in food, water, and materials get conflated with lethal amounts. Arsenault herself becomes part of an ultimately unsuccessful effort to stop Nestlé from gathering water from the Androscoggin River to bottle for their Poland Spring water bottles. (As Arsenault would point out, Poland Spring water is neither from Poland nor is it from a spring). Arsenault takes on the roles of environmentalist, creative writer, and ethnographer to show how complex and often messy it can be for communities to reckon with the memory of past environmental ills.

On a personal note, as a person of Franco-American ethnicity, I was drawn to Arsenault’s beautiful retelling of Acadian identity as it relates to her experience growing up in a mill town. Arsenault, who is of Acadian descent, proves that the environmental history of New England is inseparable from the history of Franco-Americans in New England. Some reviewers have argued that the chapters on Acadian history seemed out of place in Mill Town. Instead, I would argue that understanding the Acadian expulsion is fundamental to understanding why mills existed in New England: they relied on Franco-American labor.

I felt overwhelmed with emotion when I read Arsenault’s chapter on her Acadian ancestry. Particularly stirring is when she writes of how stories and poems like Anne of Green Gables and “Evangeline” strip Prince Edward Island and the Canadian Maritimes from the real generational trauma etched into the Acadian and Mi’kmaq communities there. At the same time, she feels distanced from her own family history, asking herself of the Acadian community: “am I also an outsider myself?”

I’ve always found myself grappling with similar questions. My family is not Acadian and I do not lay claim to the same Acadian tragedies which Arsenault eloquently outlines, but as someone with a Mémère whose father emigrated from Quebec to the mill town of Woonsocket, Rhode Island, I felt as though I had been waiting all of my life to hear someone speak about Franco-Americans in the way that Arsenault did. Do I not speak French enough? Do I even feel welcomed by the history of my own last name?

When my New England Environmental History instructor assigned Mill Town on this semester’s syllabus, I realized that in my sixteen years of education, this was the first time a professor or teacher had put any text about Franco-Americans on a required reading list. Because I grew up with this history, it’s hard for me to think of New England without Franco-Americans; yet, if I never encountered Franco-American history in my own upbringing, did my peers? When the average Joe of New England drives past a mill, do they think of the people with Mémères and Pépères who used to work there, or do they see these spaces as dilapidated buildings or renovated apartment complexes?

I’m not sure I know the answer, but I want people to read this book to understand that the environmental and cultural legacies of these mills still shape New England communities today. We live among hundreds of mill towns in New England which relied on the labor of Franco-Americans and immigrants from other countries. They now sit as brownfields in our own communities, leaving us to process their devastating environmental and cultural legacies.

Arsenault presents a stunning book which reckons with the ghosts of the long rivers which run through the mill towns of New England and beyond. The environments in many of our communities have been sacrificed for commerce, and because of this, I think we should all hear what Arsenault has to say.

Thank you