Written by: Cameron Deslaurier

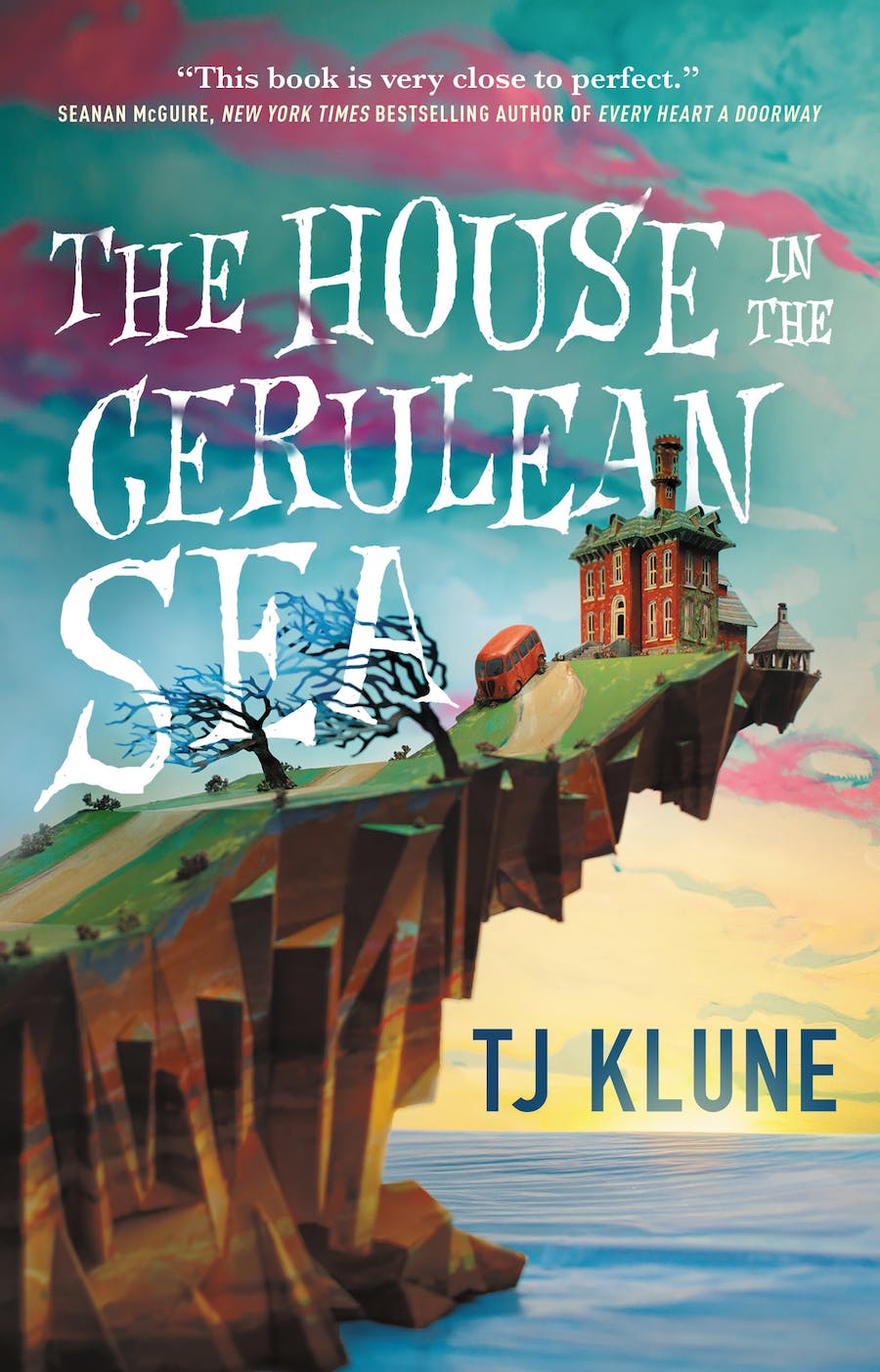

Looking for a feel-good, gay love story about finding family in the form of an orphanage headmaster, a blob of goo who wants to be a bellhop, the antichrist, and a murderous garden gnome? The House in the Cerulean Sea by Lambda Literary Award-winning author T.J. Klune is a New York Times, USA Today, and Washington Post Bestseller—and it delivers. As V. E. Schwab said, reading The House in the Cerulean Sea “…is like being wrapped up in a big gay blanket.”

The magical realism novel centers on one Linus Baker—an exceptionally average middle-aged man whose job inspecting orphanages as a caseworker for the Department In Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY) has led him to stagnation and near apathy.

Linus’ life is gray, despite how much he cares about the magical children he works to keep safe. It rains every day in the city. He never remembers his umbrella. His desk has a single personal artifact on it: a mousepad with an image of the brightest blue ocean, with the words “Don’t you wish you were here?” on it. Linus returns home after every unsatisfying day of work to feed his cat, Calliope, who barely deigns to meow at him.

Everything changes when Linus is assigned a particularly peculiar, classified case investigating an orphanage run by one Arthur Parnassus, whose own secret rivals those of the magical children he cares for. Despite initial reservations that bonding with the children will cloud his objectivity, the six rapscallions make Linus begin to feel life again in a way that he’s forgotten.

Theodore, one of the last remaining small, dragon-like wyverns, flies clumsily and is obsessed with protecting his hoard—which happens to be mostly buttons. Talia is one of the few female gnomes left and grows flowers any garden magazine would envy. Phee is a forest sprite just coming into her magic, and learning where that magic comes from. Chauncey… well, no one knows what Chauncey is or where he came from. But he’s a green blob with eye stalks, and he really wants to be a bellhop and help people instead of being seen as a monster. Sal is a Pomeranian shifter, and the sweetest of the bunch despite his imposing stature. He’s a budding writer who’s relied on making himself small to stay safe. Finally, there’s Lucy: son of Satan (we don’t say the word antichrist), and six-year-old who loves baking and old records.

The six children are initially suspicious of Linus, and he of them and their capacity for destruction. But despite his self-deprecating outlook, Linus ardently believes that magical children deserve the opportunity to live normal lives in a world that would rather not see them. It’s common to see signs saying “SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING!” and ‘seeing something’ can just mean seeing a magical child. The closer Linus gets to the children, the more he begins to see his own complicitness as a DICOMY employee in their mistreatment and marginalization.

The way Linus comes to care for the children and their caretaker is like watching watercolor spread across a charcoaled canvas. Through the children’s unmarred joy and make-believe, Linus comes to shed his own insecurities about his body and his self-declared bland personality.

Unlike many books operating under the limited timeframe trope, The House in the Cerulean Sea spends enough time in Linus’ old life that we feel the changes he experiences on the island the orphanage is located on as strongly as he does. The plot doesn’t lean on miscommunication, nor does it rely on a single ‘I screwed up’ moment for Linus to make his final decisions about if the orphanage can continue to be run, and if he has any place in it.

Linus is a somewhat plain, believable man who doesn’t turn into a fantasy-perfect hero at the end. Instead, he learns that maybe what he’s already got is just what the children—and a certain orphanage master—are looking for.

Arthur and Linus’ relationship starts with witty banter and a shared concern for the welfare of magical children, even if they come at the issue from perspectives that initially seem in opposition. Their conversations are intentional, and their flirtation is intimate in a way that relies on each seeing the other: where an offer to dance or a hand on a knee feels momentous in the way that only tenderly considered small moments can.

While not explicit, there are parallels between the way magical beings and LGBTQIA+ people in the real world are viewed, mistreated, and shoved into corners. The question of coexisting with hateful neighbors is carefully held, and the suggestion gentler than one might expect. Arthur’s willing to burn down the world to protect the children in his care, but Linus shows him that he might not have to.

I found The House in the Cerulean Sea at a time when I was wondering if joy could last in my life and if it was worth trying for. This book is a resounding, queer and life-affirming ‘yes.’ It takes the question ‘Don’t you wish you were here?’ and asks ‘Why can’t you be?’