Written by: Charlotte Ungar

Poets and writers often marvel at the mystery of creative writing, with its rich possibilities to explain how a more ‘free’ human mind may operate in ways previously unknown. Understanding their wonder is sensible, as the barriers to entry for creative writing are close to none, and yet the end product so often exceeds many other disciplines.

But at some point when a writer sits down with only a thin page of paper, pen in hand, they rely just as much on their perception of what they wish to write, as perhaps, the pen itself. And it is without a doubt that many writers dwell on themselves being walking extensions of their writing, to which they succumb to their own worst inhibitions, and their creativity reflexes in fear of judgment. Using the mind in this way is more like exhausting it rather than exercising it, because what good is a poem that is overly self-conscious of other poems?

While many of us discreetly cling to an identified standard to assess ourselves as creatives, the legacy of Russell Edson serves as a reminder that writers who write for the mere specialness of free thinking can carve out spaces within language never enacted before.

Known as the “godfather of the prose poem,” Edson’s reputation as one of the most important writers of the twentieth century is not without a reputation of insanity. This, perhaps, is due to the sheer eccentricity of Edson’s work, with its fable-like style and morbid humor mingled in-between surrealist and realist imagery. One Colorado State University professor introduced Edson’s writing to his creative writing class by prefacing, “Here’s a sample of what the most insane person in America has been thinking about in the last twenty years.”

Yet the fundamental reason why Edson’s work appears so unnervingly brillant is because his writing uncovers the tensions of contemporary society by weaving isolated ways of thinking together. For example, Edson didn’t just seek inspiration from dreams, he seized them as a tool and a way to live. Even the covers of his books boast elongated faces who only barely resemble a human. A face morphs into a moon-like crescent; a man deformed begins to sever into more deformed men, all of these force readers to interpret the limits of their own recognition in what a human may look like—to reimagine what is conceivable.

In an interview with Mark Tursi, Edson is asked how his prose poems seem so insane if Edson himself believes language is a form of sanity. In response, Edson abandons the concept of both categories of mentality, upholding genuine poetry to defy the limitations of those categories, and states, “Pure poetry is the land of languageless dreams, of mute images rising.” In the same interview, Edson continues saying, “Poetry is fun. Why burden it with the humdrum of unexplored memory in the illusion of self expression?” Upon hearing these sentiments, you might feel bewildered by the ease at which Edson associates poetry with dreams, and invalidates self expression as vain decoration. Aren’t all artists masters of expressing themselves?

What Edson pushes us to do is reject the thought of how we express ourselves, because in doing so we neglect the significance of what is already inside us, of untapped thought, of dreams. And when writers rely on their memories, it’s true many of us select our memories strategically, whether we can recognize our self-interests or not. In comparison, a dream is more untethered, more pure, like a raw sequence of words, like poetry.

The next time you find yourself staring at a conglomerate of words, thinking, “Why is this what I chose to put in the poem,” consider, “A poetry freed from the definition of poetry” as Russell Edson says. Consider that a blank brain is the best engine there is to streamlining fruitful consciousness.

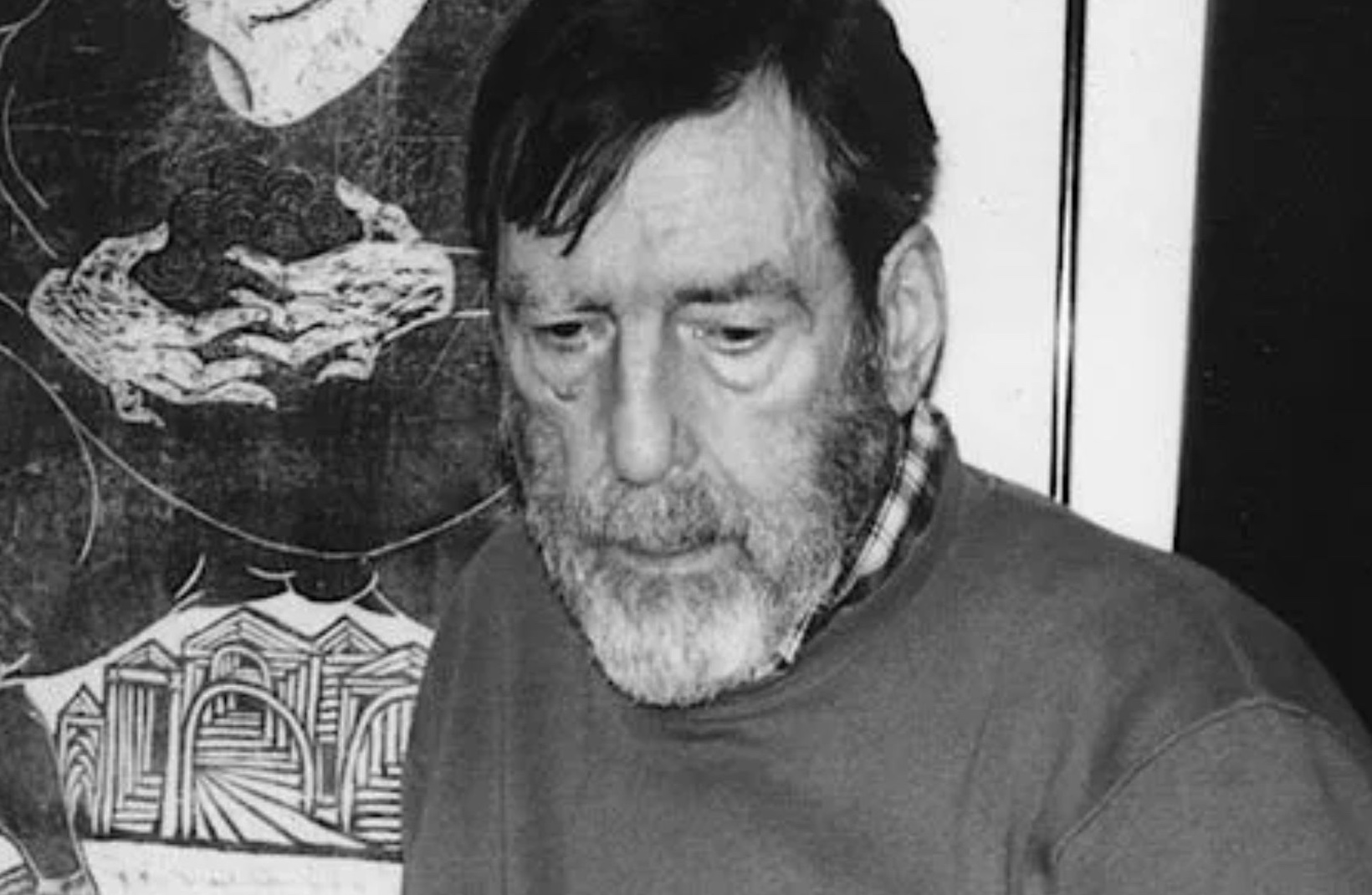

Featured Image Caption: A black and white photo of Russell Edson

You must be logged in to post a comment.