Written by: Toriana Grooms

Right now, I am taking Literature and Culture: Indigenous Horror with Dr. Kali Simmons where I have been introduced to the indigenous horror novel Bad Cree by Jessica Johns. While this discussion is not a book review per se, I will mention that the novel does a fantastic job at framing native culture, and the book’s writing strongly reflects that it was written by a native woman. After we finished the book, our class watched a video from the CBC’s Canada Reads 2024, where a book is presented, and a panel of judges comment on and critique the book. One of the most notable critiques was the complaint that the book didn’t focus enough on intergenerational trauma and missing indigenous women, but it oriented itself as more of a ghost story.

“I just didn’t get the themes you’re talking about coming through as clearly as other contemporary indigenous fiction.”

This statement was made in 2024, though it could have been stated several years prior, and my opinion would be largely the same; why must all indigenous fiction have the same archetypes to be considered publishable or readable? Why are outside groups allowed to comment on what makes contemporary indigenous fiction, aside from the author using their character(s) to reflect an indigenous person? And what about contemporary African American literature, are black experiences solely defined by systematic oppression and a singular uniform black experience? BIPOC literature is nuanced, and there should be freedom to write a storyline that doesn’t explicitly state ethnic trauma in a way that is marketable or easily digestible to the white majority.

In the case of Bad Cree, indigenous trauma, familial issues, and the exploitation of indigenous women are an essential component to the indigenous experience; however, it is also important to remember that not every piece of literature written by an indigenous person needs to highlight the same prominent cultural themes with the same intensity. I asked Jessica Johns about her experience as an indigenous author, and if she has dealt with non-POC critics attempting to stereotype and exoticize native culture. She stated that this is an issue that she has dealt with frequently, and while she believes it is important to mention topics connected to indigenous livelihood, she would also love to delve into fantasy and other literary categories without feeling she should be so restricted in presenting content.

This desire to characterize and standardize nonwhite media is greatly damaging to ethnic communities and the presentation of ethnic communities in media. “Indigenous fiction” is a genre, and there is no singular narrative to write it through. Why should novels and media with predominantly white leads get the luxury of diversity within storytelling—fantasy, sci-fi, horror—while ethnic minorities must stick within a bubble that is deemed “acceptable” for nonwhite literature? People of color should not have to curate literature to fit the mold of a non-BIPOC member’s expectations of their community.

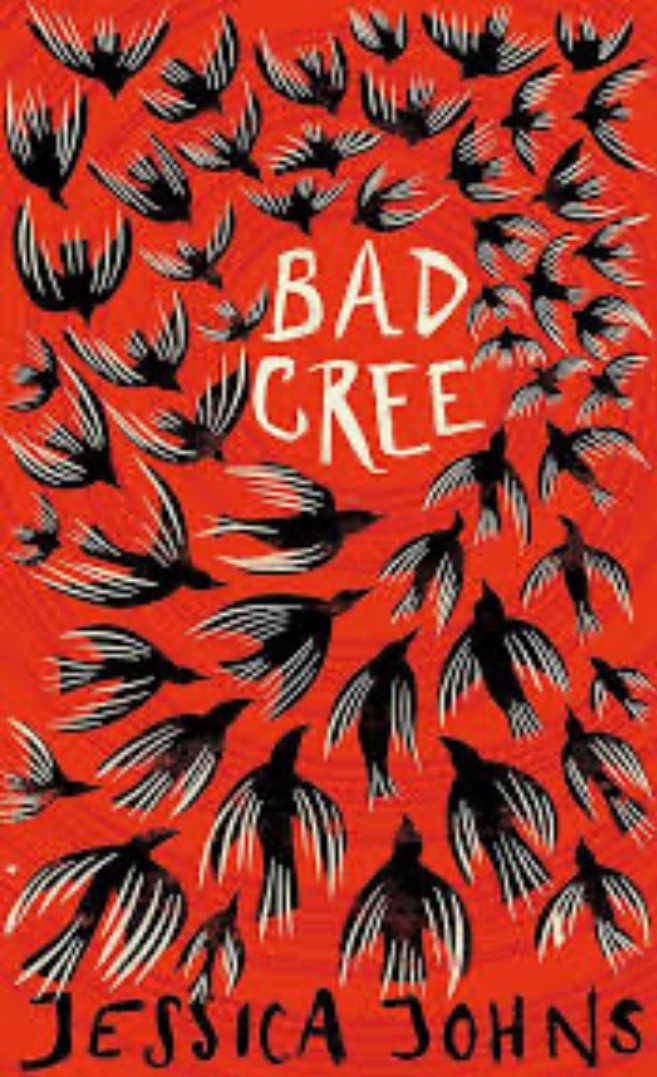

Featured Image Caption: The book cover of Bad Cree by Jessica Johns has black birds with white feathers against a red background.